Lesson 1-3: Creating an Original Arrangement for Larger Ensembles

Lesson I-1: Adding a Guitar Solo to an Existing Arrangement

Lesson I-2: Creating an Original Arrangement for a Guitar Led Trio

Introduction to Arranging for Larger Ensembles

I'm assuming that you're studying these lessons in order; therefore, let me emphasize that everything we talked about in the first two lessons of this appendix apply to arranging for a larger ensemble. Take a few minutes and do a quick review.

I studied arranging and orchestration in a night school class at a local junior college. It was a wonderful experience, one of the highlights of my college studies, and I can't recommend more enthusiastically for you to pursue a similar course. If your local junior or community college has a music department, visit it to learn more about what's available. If a course on arranging and orchestration isn't available, ask for one. In my particular case, the college needed at least 10 students to justify the course, and we were able to get about 30. Don't worry about your qualifications, because as a graduate of Mickey's course, you'll be light years ahead of most folks in areas like harmony and creating solos. Additionally, you'll find you'll have a number of different instruments that will give you many choices for your arrangements. Generally, courses like this appeal to musicians that want to learn rather than take an elective to fill out graduation requirements. Not only will you learn from the course, but you'll meet a number of musicians that have a similar interest in arranging. That's how you can have an occasional "Sax Section", or "Woodwind quintet", and they can get a versatile guitarist. I dare say that you'll make new musical friendships that will continue after the course completion. Have I sold you on the idea yet?

As the possibilities for large ensembles are practically infinite, let's talk about the group in general and your guitar part in particular. When I listen to large ensembles, I'm always reminded of an accordion effect. Rarely, does the entire group play together the whole arrangement, but rather, it plays together, then thins out while someone is soloing, comes together, thins out, etc. Arguably, the father of the modern concept of a symphony orchestra, Hector Berlioz, himself a guitarist, wrote that "the guitar is a miniature orchestra." Applying that to arranging music for guitar and ensemble, don't duplicate parts unless you have a good reason for doing so. That is to say, limit the guitar's harmony when the orchestra is playing along with the guitar. That goes for the other polytonal instruments as well.

During the "thin" sections, that is, when someone is soloing, the writing becomes identical to arranging for a trio of lead instrument, bass or rhythm section with percussion that we discussed in Lesson 2 of this appendix. The "thick" sections are what we need to concentrate on.

One technique that is easy to learn and works is to write a part for a polytonal instrument like a piano, organ, or guitar and then divide it into individual lines of music to be given to each instrument. If your harmony sounds good on the guitar, then it will sound good on any group of instruments. An advantage of having a group effort is the ability to write close spaced "chord clusters". Due to the guitar's tuning, a combination of fourth's with a Major third, playing close harmony of more than three notes becomes difficult and often physically impossible. In one of the early lessons in Mickey's course, we said that if our bass player plays a C note, and we guitarists play an E min7, the audience hears a C Maj9. We write our melody note and then we put the next closest note of the chord. We continue until we have our 4-part harmony. A simple work around is do write the guitar part of 4 notes with the melody as the highest note. Then raise the bass or the lowest note up an octave. The following example illustrates this technique:

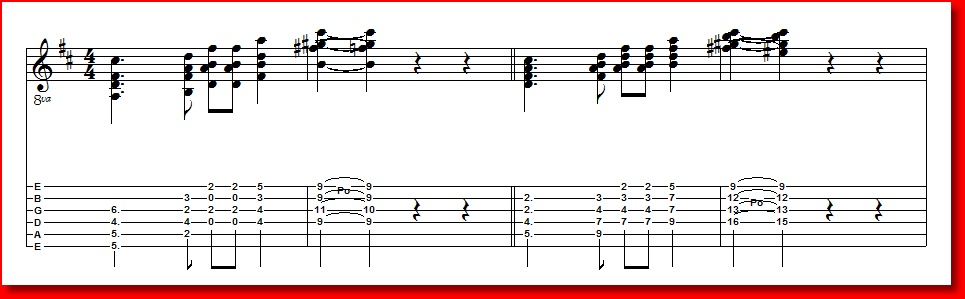

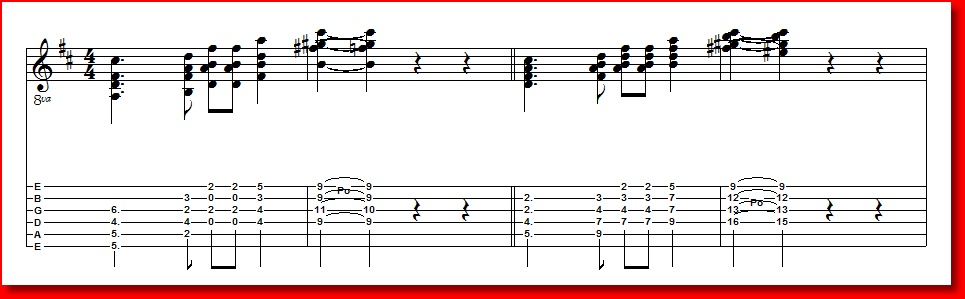

Converting Guitar Harmony to Close Spaced Harmony

This example is taken from the first two measures of the Sax section of Tommy Dorsey's "I'm Getting Sentimental Over You". In the first two measures, we have I (tonic) harmony going to VII7 harmony (or D to C#7). Using the Maj7 to Maj6 substitution, and also stylizing the melody, we write the harmony as close as it is practical on the guitar. D Maj7 to a series of D Maj6 or B min7 forms and the 2nd measure, we start with a C#7 sus4 to a C#7. Play it on your guitar. Look at the standard notation. The chords are as closed spaced as possible on the guitar (without tricks like open strings), but they still appear very open. In measures 3 and 4, we take the lowest or bass notes and raise them an octave. The standard notation shows we have as close spaced chords as Maj7 and Maj6 are. But the TAB staff shows a very unplayable-on-the-guitar chord progression. But we can play any single line there. For example, let's give the guitar the highest line, our fictional alto saxophonist the 2nd line, our fictional tenor saxophonist the 3rd line, and our fictional trombonist the 4th or lowest line. (Note the "Octave" symbol on the treble clef indicating that the notes will sound an octave lower than written.

BTW, this handy trick works in reverse as well. We can take close spaced harmony, and drop the 2nd highest note an octave and have a playable chord progression on the guitar. Using this trick over the years, I've discovered lots of chord progressions with voicings I never would have figured out on my own.

Once we harmonize the selected section, we'll divide it into lines, and match the lines with the instruments. Here a little familiarity with the range of instruments is a must. I suggest that in your Standards Portfolio, you make a folder with a name such as "Instrument Ranges". As you work with different instruments, you add their characteristics. You can also research each instrument on the Internet and add it. One additional tip is to ask instrumentalists for their input. I have a friend that is a guitarist and trombonist. When I write a trombone part, I ask him to critique it.

After creating our arrangement and cleaning up all the little "gotcha's", it's time to break it into individual parts to hand to the members of our orchestra. There are several different ways of doing this in TablEdit. Probably the easiest is to make copies of the TEF and add the instrument in the title of the copy. For example, Jose's Blues-guitar, Jose's Blues-bass, etc. In each TEF, go to Files>Options>Multitrack. Delete all the unwanted parts in that TEF by clicking on the checked boxes to remove the checks. To check your work, you can play the TEF on your computer. Although the only module displayed is the desired one, all the parts will sound in the playback.

A second method is to copy each MIDI model to a new TEF. It takes a little longer, and there is always the chance of making a mistake. However, you can edit each TEF to get rid of blank measures. Another reason for using this method is if your orchestra has Bb or Eb instruments, you're going to have to transpose those parts. When a Bb instrument, such as a clarinet, saxophone, trumpet plays a note written as a "C", it comes out a Bb. If your TEF is written in C, then on paper, your Bb instruments must be written as if they are in the key of D. Did a little light come on and you now see why we studied Bb, Eb, Ab, and Db during Mickey's course? Bb horns will have parts written in C, F, Bb, and Eb for those keys. In addition, there are a number of Eb instruments (when they play a "C", it sounds like Eb) such as soprano, alto, and baritone saxophones, alto clarinets, etc. Eb must be written (usually up) to C, Bb to G, Ab to F, and Db to Bb. Always remember that a call to the player of the Bb or Eb instrument will usually clear up an questions you may have.

Extra study: Continue listening to the great groups in the history of recorded music, not only those that feature the guitar, but other ideas. Continue with your Standards portfolio (the more you have in it, the more research material you have available. Try to find a used copy of the brilliant textbook "Arranging and Orchestration" by Russell Garcia (I know this must seem like "déjà vu", but I can't emphasize enough what a great reference this textbook is.)

Just keep it FUN!