Lesson 4

Notes to Lesson 4

When you compare Mickey's written lessons to the TEF's, you'll see that I've removed all the repeat symbols. For example, Mickey writes 6 measures with repeats for Exercise #1, and I show all 12 measures. I think that repeats sometimes cause problems in reading. To help the guitarist as much as possible, let's sacrifice a little more paper in the printer. This modus operandi is continued throughout the course and I only show repeats, if they are of the entire exercise.

Another advantage to eliminating repeats is that it's easier to do "Looping" to practice along with the midi.

Starting in Lesson 3 we have a "partner" playing the example with us. For the MIDI playback in TE, I have given both parts, or modules the sound of an acoustic steel string guitar. My motives were simple, I just didn't want to detract from the actual lesson. You may decide that Acoustic Steel String Guitar is not a sound you either wish to imitate or play along with. Here's how you can "customize" that voice in each exercise:

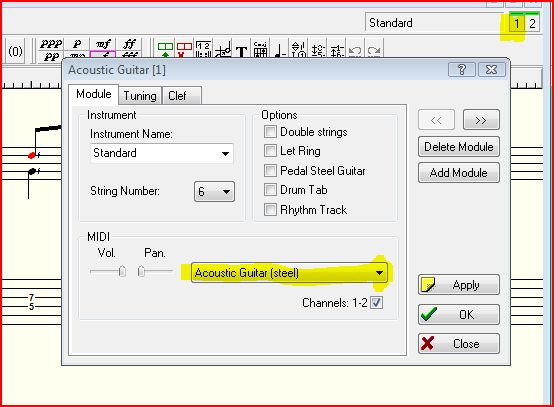

In the main TablEdit window, DOUBLE LEFT CLICK on the desired MIDI module box. Refer to the illustration and note that I've highlighted the MIDI Module 1 "Standard" box.

Selection of MIDI Voice

Left click on the Down Arrow of the Voice selection box. Note I've highlighted it and emphasized the "Down Arrow".

A list of instruments will appear. Chances are we'll use one of the guitar voices. Click on the desired voice. If one wishes a 12-string guitar, click in the Double strings box just above the MIDI Voice Box.

Then either click on the Apply button (this allows us to do more editing of these functions), or the OK button (this accepts our selection and closes the window.)

If we selected "Apply" and wish to change the 2nd module, left click on the Right Navigation Arrow in the upper right hand corner of the window.

For the Chords and Rhythm Section of this course, we probably can accept the Acoustic Steel String Guitar voice without too many complaints. But when we start in the solo section, we may wish to make the solo guitar voice an electric guitar voice for contrast, and a more realistic sound as the vast majority of us play electric guitars.

You now are as much of an expert in TablEdit's MIDI modules as this course requires. For additional information, please consult the Help Files which also have a tutorial.

As I mentioned in Lesson 3's notes, Lessons 3 and 4 are the heart and soul of every lesson to follow. Spend as much time as possible with these two lessons and you'll benefit in future lessons.

Note we're still working with Group A chords. That is, chords where the root of the key or the tonic note is found on the 6th string, such as G, F, Ab, and Bb.

Let's start thinking in terms of the famous (or "infamous") numbering system, using Roman Numerals. There are many variations on this system in the musical world, and what I will be referring to in this course is a custom version where I've taken some of the best features of several systems to make one system that is easy to follow and easy to transition to another, such as "The Nashville System."

I've chosen Mickey's example 3 from this lesson. G is the tonic or root chord so it's going to be "I", with G Maj7 and G Maj6 as I Maj7, and I Maj6 (or more commonly "I6".) The G7 would be I7. C is IV, and C minor would be lower case "iv". In G, a D minor, as C minor, doesn't naturally occur (F isn't in the G scale, it's F#), and D Major is the dominant or V. But as we're substituting D minor colored chords for G7 (which also doesn't naturally occur in a G major scale), we can call the D minor chords "v7 and v6". The G# dim is a "#i dim7" (remember diminished and minor take lower case.) The Bb min7 would be "biii7", A min7 would be ii7, and the D13b5b9 would be a V13b5b9. If we can begin to think in these Roman numerals, then we can do our transpositions in our heads, or on the fly. Here's a little test: we're in the key of Db Major, and we see #i dim7. What chord would we play? I'll bet everyone taking this course immediately said "D dim7". But keep it a secret!

One additional comment: Note that in Group A chords, Mickey uses the V13b5b9 chord as his "workhorse" most colored dominant chord form. The form looks very much like a barred "F" form with a couple of blues notes added, don't you think? An easy way for me to remember where this chord is located is to remember that it is a Group A chord and will normally resolve to a Group A tonic chord, such as D13b5b9 to G Maj7. The 6th string note will ALWAYS be one fret higher than the tonic... in this example 4th fret to 3rd fret.

Continuing our analysis of Example 3, note that starting with the C min7 in measure 4, the bass line is a chromatic descent - 8th fret to 7th, to 6th, to 5th, to 4th, to 3rd.

Example 1 gives us substitutions for I and IV, V7, V7 to I, and ii, iii, and vi chords.

Example 2 gives us six (including the standard) turn-arounds. Let's discuss turn-arounds a little. A turn-around is a way to end a "musical phrase." This term seems to have come from Blues musicians, but is now practically universal. Most classical musicians call it a "cadence" and they have adjectives to describe various cadences. For example a I - IV - I turn-around is known as the "Amen Cadence" as it is used in religious music at the end when the congregation sings "AMEN" (I'm sure the next time you hear Chet Atkins' version of the Nine Pound Hammer, you'll sing ".....when the wheels won't roll. Amen." Chet plays a "I - IV - I" turn around between the verses.) Wikipedia has a lot of interesting information about the classical definition of cadence. Turn-around is a much friendlier and easier to understand term and that's what I'll use in discussions in this course.

Turn-around also describes the last two measures of a common 12 bar blues tune. Measure 11 is a I chord and Measure 12 is a V7 chord to build interest in returning to the I chord of Measure 1. That's the turn-around, returning to Measure 1. It also can just be two measures of a I chord. Often in other musical forms we end an 8, 16, or 32 measure phrase with two measures of the I chord. We can freely substitute any one of the 6 turn-arounds shown. All of us know tunes in the key of G. Try playing one of these and at each turn around point, substitute one of the six turnarounds Mickey gives us. Don't be shy or timid about using the standard forms as well as the new ones. If you know 2 tunes in G, I'm willing to bet that inserting the turn-arounds in the 2nd one came easier than the first. Additionally, in a tune with several measures of the same harmony, such as tonic or "I" harmony, we can use a turn-around as a substitute to kill the boredom of the repeated chord. Turn-arounds are an incredibly important tool for us and I encourage you to look for turn-arounds in any of the tunes you'll work on in the future.

Example 4 sounds to me like about 50% of all tunes that came from the 20's and 30's. When I first heard it I started whistling the great old Harold Arlen standard "Between The Devil and the Deep Blue Sea." It also fits a bunch of Gershwin tunes and Rodgers and Hart classics, too.

Example 5 is the very first 12-bar blues chord progression Mickey gives us. All of us know a blues tune that we can play in the key of G, so hum it or sing it while playing this progression. More than likely you'll want to use a different strum than our "Plain Jane Vanilla" lick. Use your imagination and perhaps you'll be pleasantly surprised at how fresh your Blues tune becomes. This turn-around is one you'll want to use time and again. By the way, why don't we substitute some of the 6 turn-arounds of Example 2 in Measures 11 and 12 of this example?

As this course continues, you're going to find yourself inventing your own turn-arounds, just because it's fun to do! Don't forget to share them with us.

The blues are an important part of modern music not only in the western world, but in all parts of the world. It's not uncommon to hear a sitarist in India playing a Raga and inserting a blues note here or there that 100 years ago would have been unheard of. Commit this exercise to memory and compare it with the other blues progressions we'll study later on. A suggestion is to make a folder where you are storing your course files and dedicate that folder to Blues progressions. If your experience with the Blues is minimal, analyze the standard chord progression , using I, IV, and V (sometimes a ii is thrown in as well), how many measures of each, and the obligatory turn-around in the last two measures. This is the mother-lode of popular music for the last 100 years. When you and your friends get together and "jam", listen to the comments like "Where did you get that GREAT chord progression?"

Just keep it FUN!