Appendix I - Introduction to Arranging

Lesson I-1: Adding a Guitar Solo to an Existing Arrangement

Lesson I-2: Creating an Original Arrangement for Guitar, Bass, and Percussion

Lesson 1-3: Creating an Original Arrangement for Larger Ensembles

As brand-new graduates of the Mickey Baker School of Jazz and Hot Guitar, we surely want to practice and perform our newly developed skills. We have lots of ways to do that:

Join a local orchestra/big band

Join a smaller combo or band

Create our own band or combo

Play solo or solo with an electronically generated backup, such as Band-In-A-Box or a rhythm machine.

Perhaps we're satisfied with just being a part of a group and accept the arrangements provided by the band leader and his arranger. But sooner or later the bug to create our own arrangements bites us. Even if you aren't the designated group leader or are paid for arranging, your arrangements will be accepted for at least an audition, as all bands and groups are constantly looking for new and fresh material. The more professional your arrangements are, the more popular they will be. Here are some tips to help guide one in the study of arranging.

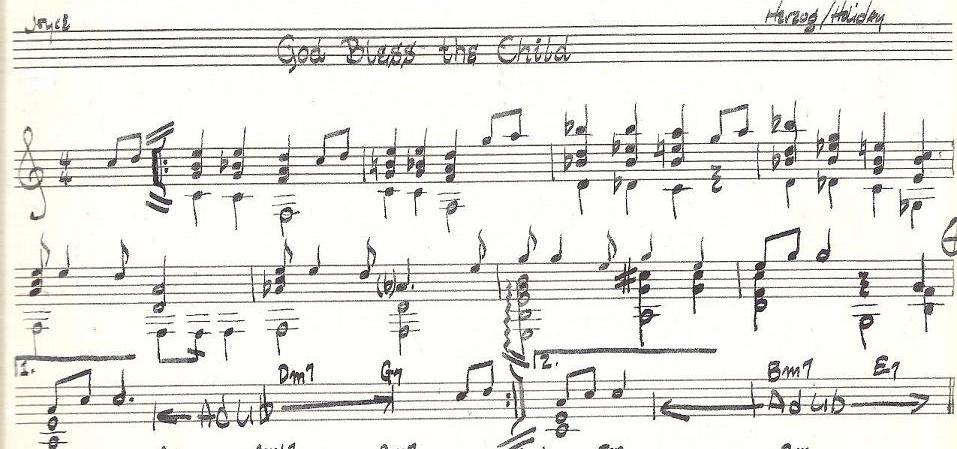

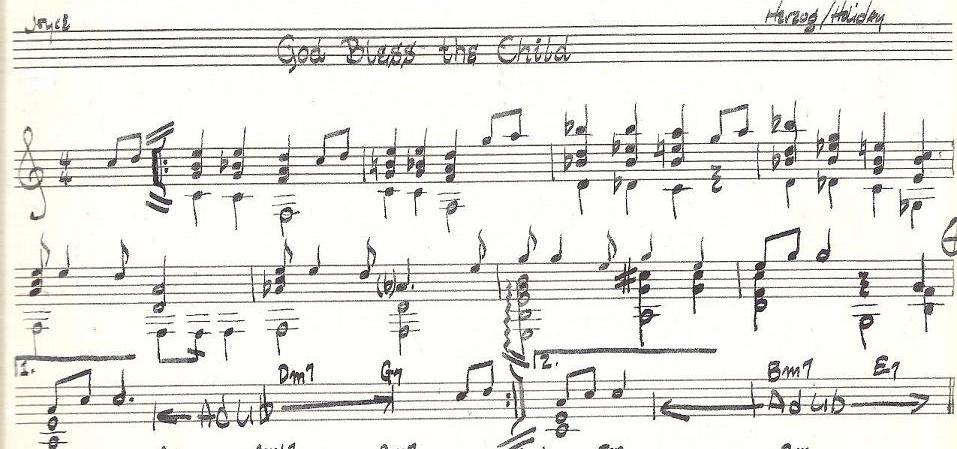

Before computers and music writing editors, arrangers had to study calligraphy to hand-write the parts. And to this day, a professionally scribed manuscript on stiff stock, using black India Ink is a welcome relief from the pages printed by computers on translucent paper with ink that is grayer than black. Any shop that sells calligraphy materials can obtain a pen with a music writing "nib". In a short period one can become very proficient with this pen. Slightly turning the pen will provide either fat or thin lines and before you know it, you'll be receiving compliments on your penmanship. Here's a sample from a manuscript I did in 1975 for a college musical:

Example of a Handwritten Score Using India Ink and a Pen with a Music Nib

With just a little practice, I'm certain you can create manuscripts certainly as good if not quite a bit better than my efforts. This particular example is a compromise between being as professional as I could and a very tight deadline (four hours as I remember). With a little more time and concentration, and perhaps a straight edge, one can truly mimic and approach the quality of a typeset manuscript.

With a reasonably good printer and a dedicated black ink cartridge, we can get some amazingly professional scores generated by our trusty old friend, TablEdit. A trick that works for me is to have my cartridges filled (that is to say, "refilled") by a local print cartridge refiller. Refilling kits are also plentiful, but I've had better success with buying ink and letting them use their tools for the job. It's not very expensive, especially if you are supplying the ink.

Right about now you may be asking yourself "I have the musical skills such as reading standard notation, I am proficient with TablEdit/handwriting a score, and I have some musicians that I can write for. What do I do next?" The following three lessons hopefully will give you some ideas:

Lesson I-1: Adding a Guitar Solo to an Existing Arrangement

Lesson I-2: Creating an Original Arrangement for a Guitar Lead Trio

Lesson I-3: Creating an Original Arrangement for Larger Ensembles

Here are some general rules that work almost always:

Remember: IT'S ABOUT THE MUSIC, not you and your ego.

Don't let polytonal instruments (guitars, harps, pianos, etc.) clash. For example, don't give chord symbols to two guitars and tell them to use their substitutions. Instead write parts that complement the two or more instruments.

Don't write chord solos or 2-part solos (like a melody and stride bass-line) for polytonal instruments when the whole group is playing. Put the chord solos into interludes where the music "thins out."

Develop your musical taste by listening analytically to groups and making a decision as to what works and what doesn't from your listening.

Drum solos and Bass solos can be effective, but generally one must apply the Brylcreme Law: "A little dab'll do ya!". Pacify your bass player by writing interesting parts for him. The easiest way to pacify your drummer is to have him neutered and put on tranquilizers. (Just joking with a little drummer humor!) Nothing makes a group standout more than a tasty, two-fisted drummer.

Use discretion when pairing instruments. For example, it's difficult to balance trumpets and flutes together. Instead, give them "call and response" parts. To develop a feel for this, listen to Dixieland groups, especially when they are improvising 3- and 4-part harmony.

Listen to nonmusicians that love music. Their advice will be more about the quality of the music than the quality of the musician. Musicians called to critique often let personalities and egos interfere with their criticisms. A nonmusician will tell you if he likes something or not.

Remember: IT'S ABOUT THE MUSIC, not you and your ego.

We really haven't scratched the surface in the wonderful study of Arranging and Orchestration in this appendix's three lessons. This is meant only as an aid to help one begin his personal study. Good luck and remember that the hardest one you'll ever do is the first one. With those words of wisdom, let's crank out at least 10!!!

Extra study: Continue listening to the great groups in the history of recorded music, not only those that feature the guitar, but other ideas. Continue with your Standards portfolio (the more you have in it, the more research material you have available. Try to find a used copy of the brilliant textbook "Arranging and Orchestration" by Russell Garcia. Check out community colleges and night schools for courses in Arranging and Orchestration. Generally, courses like this appeal to musicians that want to learn rather than to those that need an elective to fill out graduation requirements. Not only will you learn from the course, but you'll meet a number of musicians that have a similar interest in arranging. That's how you can have an occasional "Sax Section", or "Woodwind quintet", and they can get a versatile guitarist.

Just keep it FUN!